Obtain news and background information about sealing technology, get in touch with innovative products – subscribe to the free e-mail newsletter.

Into the World With a Sample Case

Globalization is not a new phenomenon. Around 1850, a businessman built a global sales network, procured raw materials from three continents and organized supply chains. But he had some help from reindeer. His product: pencils.

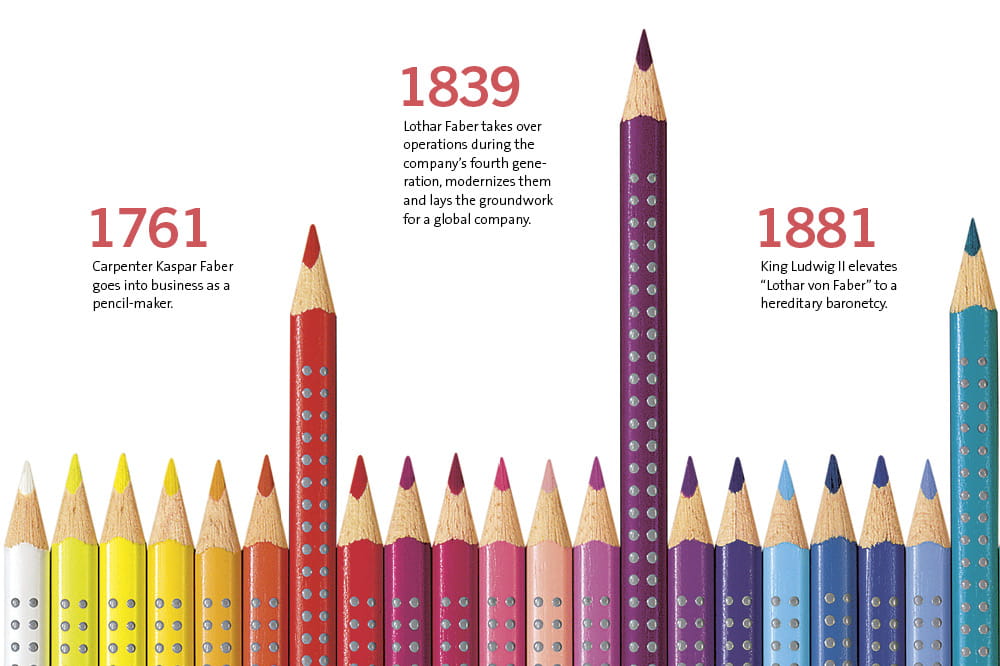

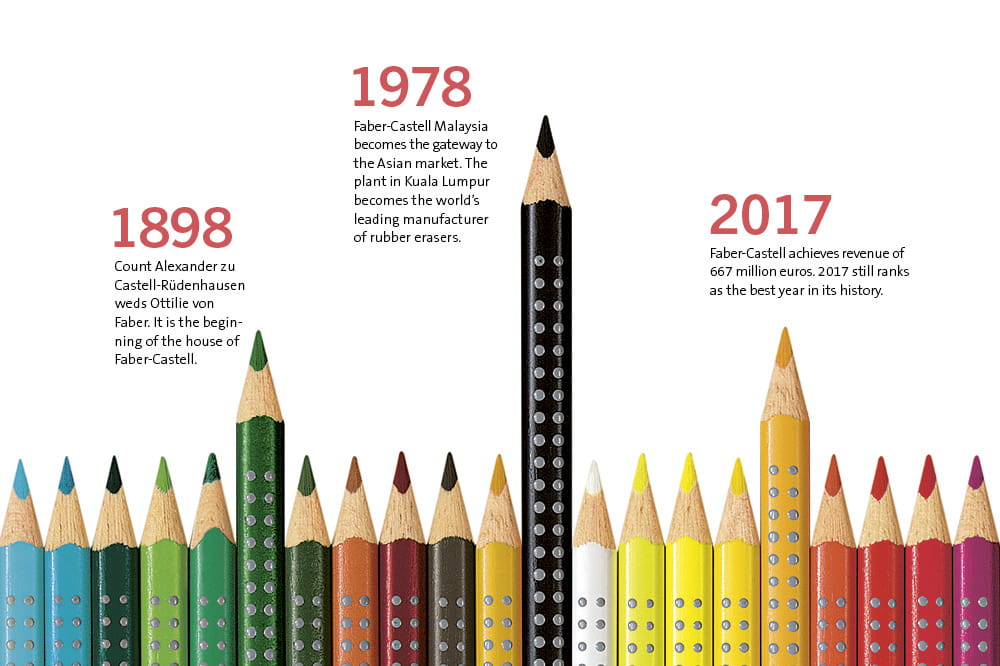

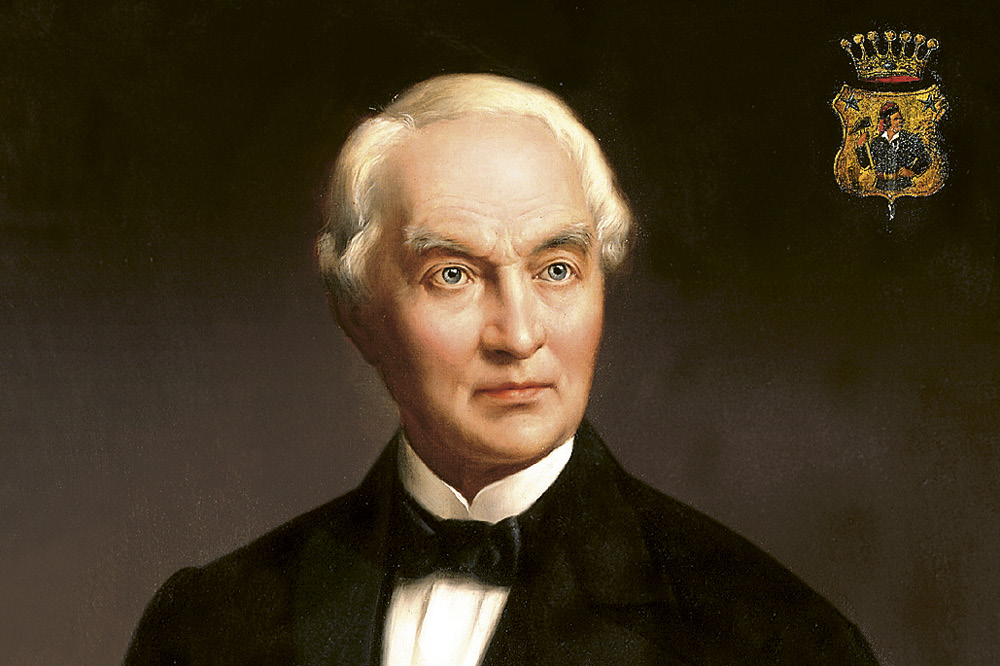

Globalization is not a new phenomenon. Around 1850, a businessman built a global sales network, procured raw materials from three continents and organized supply chains. But he had some help from reindeer. His product: pencils. When Lothar Faber took over his parents’ business in 1839, it was just a small pencil factory in Stein, a Franconian town just outside of Nuremberg. Within a few decades, he turned it into a global company – in the fullest sense of the term. It was an era when work on the Suez Canal was just beginning, Britain’s Queen Victoria was just ascending to the throne, and steam engines were gradually finding their place in industry. It took 100 hours to travel from Nuremberg to Zürich, Switzerland, a length of time comparable to a global trip today.

“Paris, London, New York”

Pencils were an up-and-coming product, but competitors, especially from England, were achieving higher quality than the craft businesses around Nuremberg. As a young man, Faber went into training in Paris. “In this large, global city […] I gained insights into the entire commercial world,” he noted later. He familiarized himself with global economic interrelationships and became a business traveler. As early as 1843, he traveled to St. Petersburg with a sample case full of pencils under his arm. He established sales subsidiaries abroad for the family-owned company. His brother Eberhard Faber was dispatched to New York in 1849, and locations in London, Paris, Vienna and St. Petersburg followed. Lothar Faber wanted to create a global business – “with the harmonious collaboration of the entire intelligence of the houses in Stein, Paris, London and New York,” he wrote. He also understood that increases in sales can only be based on quality. In 1865, Eberhard Faber identified the right kind of wood in the cedar forests on Cedar Key, an island off the coast of Florida. The wood was processed in a sawmill and shipped to Germany. During the American Civil War, he decided to establish a special pencil factory in Brooklyn. Relatively cheap pencils were made there, and the more expensive products continued to be imported from Germany.

Faber-Castell

Groundworker for a global company: Baron Lothar von Faber *1817 †1896 ©Faber-Castell Archive

In 1758, journeyman carpenter Kaspar Faber set up shop in Nuremberg, where a number of pencil craftsmen were already located. The demand for writing instruments rose steadily in the coming decades, in part due to the introduction of mandatory school attendance. Lothar Faber, a member of the fourth-generation in the business, turned the craft operation into a global enterprise and “Faber” into a brand. Through a marriage into nobility, “Castell” emerged as part of its current brand name. Today, the company generates nearly 600 million euros in revenue and produces about 2 billion pens and pencils each year, making it the world’s largest manufacturer of writing instruments.

Graphite From Siberia

At about this time, a French businessman discovered graphite deposits of extraordinary quality in Siberia. This had a crucial impact on the quality of pencils since pure graphite leaves a darker mark and is softer for writing. Lothar Faber seized the moment, financed the mine and secured exclusive rights to it. The graphite was extracted in an inhospitable region and then transported thousands of miles by reindeer through pathless wilderness, before being loaded on ships or trains bound for Germany. The construction of the trans-Siberian railroad only began in 1891. Today it may seem to have been an incredibly complicated investment, but it protected the company against fluctuating prices and allowed unimagined leaps in quality. The new “Siberian pencils” conquered the world market as a “pinnacle of uniformity, purity and unchanging hardness,” as an advertising brochure put it.

Bound for New Zealand, Argentina and Beyond

Amid all these efforts, Lothar Faber decided to have the company’s name, “A.W. Faber” (recalling his grandfather Anton Wilhelm), printed on the pencils, and the first branded writing instrument was born. Product catalogs, labels, pencil cases, and an expanded selection also emerged at this time – as did advanced production systems such as the roller mills used to grind the graphite and dyes to an especially fine degree. Lothar’s brother Johann, who would launch his own pencil company in his later years, took business travel to new heights in the 1880s, sending his staff on true global voyages, to destinations ranging from Sri Lanka to Australia and New Zealand, all the way to South Africa, Argentina and Egypt. “Pioneers and travelers from the Johann Faber company are active in every country of the civilized world,” a commemorative publication stated. The travel was by ship; it would be a decade before Otto Lilienthal made the first successful gliding flight. The first airline only crossed the Atlantic in 1939.

When Count Alexander von Faber-Castell, Lothar’s successor, traveled to New York by fast steamer in 1909, the arrival of the highly advanced ship was even worth an article in local newspapers – including the mention of the “pencil king,” as the businessman was known. The foundation for the success of the pencil-making enterprise based in the small town of Stein near Nuremberg had long been laid. Today, Faber Castell has around 8,000 employees, production facilities in 10 countries, and sales offices in 22. The wood now comes from Brazil, where the company has its own cultivated and managed forest. It all sounds very modern and global, and that’s what it is – just like Lothar Faber’s factories were more than 150 years ago. Globalization was even possible before the age of aircraft and the Internet. And you could always count on reindeer in a pinch.

This article originally appeared in ESSENTIAL, Freudenberg Sealing Technologies’ corporate magazine that covers, trends, industries and new ideas. To read more stories like this, click here .

More Stories About Sustainability